Prologue

Fat flakes blew into his face, cold wet kisses on his cheeks and eyelids. Last time there had been a winter like this, he’d been a wee boy and all he remembered was the fun – sledging down the big hill, throwing snowballs in the playground, sliding across the frozen lake in the park. Now, it was a pain in the arse. Driving was a nightmare of slush and black ice. Walking was worse. He’d already wrecked his favourite pair of shoes and every time he took his socks off, his toes were wrinkled pink sultanas.

But there were advantages. No one would ever know he’d been here. His footprints would be erased within the hour. There was nobody else on the street. All the curtains were drawn tight to keep the night out and the heat in. The children were indoors now, their every outdoor garment drying on kitchen pulleys and steaming clothes horses after a day in the snow. Everybody else was huddled in front of the TV. There had been enough snow this January for the novelty to have worn off. Even the corporation bus he’d overtaken on the main drag had been empty, a ghost ship in the night. The only people he’d passed had been a couple of die-hards headed for the pub. There was an eerie stillness in this side street, though. The snow suffocated the engine noise from the few vehicles that had braved the blizzard. He felt like the last man standing.

Head bowed against the weather, he almost missed his destination. At the last moment, he realised his mistake and wheeled abruptly into the lobby of the tenement close. He took a deep breath, brushing the snow from his eyebrows.

He climbed the stairs, rehearsing what he’d been planning all day. He was standing on the edge of the road to nowhere. Maybe it was late in the day to start thinking about protecting his future, but better late than never. And he’d figured a way out. Maybe more than one.

It wouldn’t be easy. It might not be straightforward. But he deserved better than this.

And tonight, there was going to be a reckoning.

1

It started badly and only got worse. Blizzards, strikes, unburied bodies, power cuts, terrorist threats and Showaddywaddy’s Greatest Hits topping the album charts; 1979 was a cascade of catastrophe. Unless, like Allie Burns, you were a journalist. For her tribe, someone else’s bad news was the unmistakable sound of opportunity knocking.

Allie Burns stared out of the train carriage window at white, broken only by a line of telegraph poles. They were miraculously still dark on one side, sheltered from the blustery wind whipping the snow in sudden flurries. The train sat motionless, trapped in mid-journey by drifts blocking the tracks. She glanced across at Danny Sullivan. ‘How come winter always brings Scotland to a standstill?’

He chuckled. ‘It’s just like Murder on the Orient Express.

Stuck on a train in a snowdrift.’

‘Only without the murder,’ Allie pointed out. ‘OK, only without the murder.’

‘And the luxury. And the cocktails. And Albert Finney in a hairnet.’

Danny pulled a face. ‘Picky, picky, picky. Anybody would think you were on the subs’ table, fiddling with my commas and misrelated participles.’

Allie laughed. ‘I don’t even know what a misrelated participle is. And I doubt you do.’

‘I did once, if that counts?’

They subsided into silence again. They’d met unintentionally on the freezing platform of Haymarket station on the second day of the year, colleagues returning to work after spending Hogmanay with their families. There were plenty of her fellow hacks Allie would have hidden behind a platform pillar to avoid, but Danny was probably the least objectionable of them. If he was sexist, racist and sectarian to the core, he’d done a good job of hiding it. And there was no escaping the fact that after time spent with her parents, she was desperate for any conversation from her own world. The nearest she’d come was the first paper of the year, with its coverage of the International Year of the Child, an imminent lorry drivers’ strike and cut-price blouses in Frasers’ sale.

She’d met up with a couple of school friends for a drink in the village pub, but that had been no better. The chat started awkward and stilted, veered on to the comforting common ground of reminiscence, then backed into a cul-de-sac of gossip about people she didn’t remember or had never met. The past few years seemed to have severed her from old acquaintance.

As the train had pulled out of Kirkcaldy on the first leg of the journey back to Glasgow, Allie had felt the lightness of reprieve. She’d waved dutifully to her parents, standing on the snowy platform. They’d driven her the eight miles to the station from the former mining village of East Wemyss where she’d grown up, and she wondered whether they shared her sense of relief.

They had nothing to say to each other. That was at the heart of the discomfort she felt whenever she returned home. She’d slowly come to the realisation that they never had. Only, when she was growing up, that lack of connec- tion had been masked by the daily routines of work and school, Girl Guides and bowling club, Women’s Guild and hockey team.

Then Allie had gone to university in another country and been parachuted into life on Mars. Everything in Cambridge had been strange. The accents, the food, the expectations, the preoccupations. She’d quickly assimilated. She believed she’d found her tribe at last. Three years flew by, but then she was unceremoniously cast adrift.

And now, after two years in the North-East of England learning a trade, she was back in Scotland. It wasn’t what she’d planned. She’d been aiming for Fleet Street and a national daily. But the news editor on her final training scheme post was an old drinking buddy of his opposite number on the Daily Clarion in Glasgow. And it was a national daily, if you counted Scotland as a nation. The strapline on the paper said, ‘One adult in two in Scotland reads the Clarion’. The wags in the office added, ‘The other one cannae read.’ Strings had been pulled, an offer made. She couldn’t refuse.

She’d had five years of a sufficient distance to keep her visits home to a minimum. But now it was impossible to avoid the significant dates. Birthdays. Family celebrations. And because it was Scotland, Hogmanay.

Which meant three evenings of endless Festive Specials and musicals – Oliver!, My Fair Lady, Half a Sixpence. She’d wanted to watch Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine in The Apartment, but once her mother had read the brief summary in the newspaper listings, that had been firmly off the agenda. Allie didn’t want to revisit the torture so she simply said, ‘How was your New Year?’

Danny scoffed. ‘Like every New Year I can remember. We’ve got the biggest flat, so everybody piles in to ours. My dad’s got five sisters – Auntie Mary, Auntie Cathy, Aunty Theresa, Auntie Bernie and Auntie Senga.’

Allie giggled. ‘You’ve got an Auntie Senga? For real? I thought Senga was just a joke name?’

‘No. It’s “Agnes” backwards. She was baptised Agnes, but she goes by Senga. She says, anything to avoid being called Aggie.’

‘I get that. So your five aunties come over?’

Danny nodded. ‘Five aunties, four uncles and assorted cousins.’

‘Only four uncles?’

‘Yeah, Uncle Paul got killed at his work. He was crushed by a whisky barrel in the bonded warehouse down at Leith.’ He pulled a face. ‘My dad said it might have had something to do with a significant amount of the whisky being inside Uncle Paul at the time.’

‘So you have a big family party?’

‘Yep. Same every year. The aunties all do their specialities. Theresa borrows the big soup pot from the church and makes a vat of lentil soup. Mary does rolls on potted hough. Cathy bakes the best sausage rolls in Edinburgh, my mum makes meat loaf, Bernie brings black bun that nobody eats, plus shop-bought shortbread, and Senga produces three flavours of tablet.’

‘Bloody hell, that’s some feast.’ He didn’t look like someone who existed on that kind of traditional Scottish diet. Danny was slender as a greyhound, with the high cheekbones, narrow nose and sharp chin of a medieval ascetic. Only his tumble of collar-length curls made him look of his time.

He grinned. ‘No kidding. There’s enough in the house to feed half of Gorgie. And enough drink to open our own pub.’

‘So what do you do? Eat and drink and blether?’

‘Well, we eat and drink and then everybody does their party piece. That keeps us going till it’s time to turn on the telly for the bells. And then Dad puts the Corries on the record player and it just gets more raucous. A few of the neighbours come in to first-foot.’

‘Sounds like a form of self-defence!’

Danny shrugged. ‘It’s a friendly close. What about you?’ Allie was spared from answering when the door at the end of the carriage clattered open and the conductor staggered through, loaded with a pile of blankets. As he approached, he distributed them among the handful of other passengers. ‘We’re going to be stuck here a while yet,’ he announced, a gloomy relish in his voice. ‘We’ve got to wait for the snowplough to get here from Falkirk and it’s making slow progress, I’m told. And the heating’s went off. Sorry about that, but at least we’ve got some blankets.’ He handed each of them a coarse grey blanket that felt more suitable for a horse than a human. Allie wrapped it around her, nose wrinkling at the smell of mothballs. ‘Are you feeling the cold?’ Danny asked.

‘Not really. But now the heating’s off, we’ll lose our body heat pretty quickly.’

He eyed her across the narrow gap between their seats. ‘If you came and sat next to me, we could share the blan- kets. And the body heat.’ He gave her a wide-eyed smile.

‘I’m not trying anything on. Just being selfish. Look at me, there’s nothing of me. I really suffer with the cold.’

There was no denying that he was well wrapped up. Walking boots, corduroy trousers tucked into thick woollen socks, chunky polo-neck sweater peeping out of his heavy overcoat. Woolly gloves, and a knitted hat sticking out of a pocket. Allie didn’t think she’d ever seen anyone better equipped for the cold. Not even her grandfather, a man addicted to being out in the fresh air whatever the weather. A lifetime of the coal face would do that to you. ‘OK,’ she said, pretending a reluctance she didn’t feel. He was probably the only man in the newsroom who didn’t give off a predatory vibe. Arguably, you had to have the instincts of a predator to be a good reporter. But equally, you should know when to turn them off.

Allie swapped seats. They fussed with the blankets till they’d constructed a double-thickness shroud around themselves. ‘What shift are you on next?’ she asked him.

‘Day shift tomorrow. You?’

She pulled a face. ‘I’m supposed to be on the night shift tonight. Unless that bloody snowplough gets a move on, I’m going to be in big trouble.’

‘You’ve got time. It’s barely gone three. And even if you don’t make it in on time, you’ll not be the only one. You working on anything or just the day-to-day?’ He spoke with a casualness that begged the return question.

‘Waiting for the next news story to drop. You know what it’s like on the night shift. What about you?’

He smiled. ‘I’ve been chasing a big one. An investiga- tion. I’ve been on it for a few weeks, in between chasing ambulances. I got a whisper from somebody who didn’t even know what he was telling me and I’ve been trying to bottom it ever since. Mostly in my own time. Grunts like you and me, we’re not supposed to do stories like this. We’re supposed to pass it on to the news desk and let one of the glory boys lead the charge. We get to do the dirty work round the edges, but we don’t get the bylines.’

It was no less than the truth. There was a cohort of reporters who had titles – crime correspondent, chief reporter, education correspondent, court reporter and half a dozen others. When the lower orders uncovered a big story, it would immediately be snapped up by one of the guys who could claim it for his fiefdom. ‘So how did you hang on to it?’ ‘I haven’t told anybody about it yet,’ Danny said simply. ‘I’m holding on to it till it’s too far down the line for anybody to take it off me. But it’s dynamite.’

Allie felt a pang of jealousy. But it wasn’t directed at Danny. It was more a longing for a major story of her own. ‘What’s it about? When’s it going to be ready?’

‘Soon. All I need is the last piece of the jigsaw. Next long weekend, I’ve got to make a wee trip down south and find the final bits of sky.’

So, not long then. The Clarion staff worked four long shifts per week, a pattern that was so arranged that it gave them five consecutive days off every three weeks. Allie still hadn’t entirely worked out how best to use the time, though until the winter had set in she’d been developing a taste for hillwalking. But she was working up to buying a flat and she could see an endless vista of decorating and home improvement in her future. ‘Good for you. If you need a grunt—’

Again the door clattered open. This time, the guard was red-faced and agitated. ‘Are any of youse a doctor?’ He looked around, desperate. ‘Or a nurse?’

Before anyone could respond, from behind him, a wom- an’s scream split the air. ‘I’m going to fucking kill you, ya bastard.’

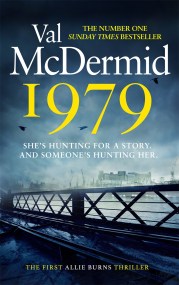

1979

by Val McDermid

THE FIRST IN A THRILLING NEW SERIES FROM THE QUEEN OF CRIME, AND AN INSTANT SUNDAY TIMES BESTSELLER

'McDermid is at her considerable best' GUARDIAN

'An irresistible and palpable journey' PATRICIA CORNWELL

The shadows hide a deadly story . . .

1979. It is the winter of discontent, and reporter Allie Burns is chasing her first big scoop. There are few women in the newsroom and she needs something explosive for the boys' club to take her seriously.

Soon Allie and fellow journalist Danny Sullivan are exposing the criminal underbelly of respectable Scotland. They risk making powerful enemies - and Allie won't stop there.

When she discovers a home-grown terrorist threat, Allie comes up with a plan to infiltrate the group and make her name. But she's a woman in a man's world . . . and putting a foot wrong could be fatal.

THE NEXT ALLIE BURNS THRILLER, 1989, IS AVAILABLE TO PRE-ORDER NOW

__________

'A brilliant novel by a supremo of the genre at the height of her powers. A cast of engaging new characters promise to make this an unmissable new series' PETER JAMES

'Remarkable and compelling . . . the Queen of Crime has delivered another masterpiece' DAVID BALDACCI

'Val McDermid is the absolute QUEEN. Allie is a fabulous character, I'll go wherever she takes me and I'm dying to see what she does next' MARIAN KEYES

'Packed full of Val McDermid's trademark brilliance, 1979 is a thrilling snapshot of a fascinating era' JANE HARPER

'Unrivalled. Unmissable. Unforgettable. 1979 is Val McDermid at her nail-biting, heart-rending best' CHRIS WHITAKER

'McDermid was a newshound at the time and it shows . . . Her best book in years' THE TIMES, BOOK OF THE MONTH

'Allie Burns is off to a flying start, and well worth following down the decades' THE SCOTSMAN

'A brilliant thriller, as well as a perfect snapshot of the social and political issues of the time' LINWOOD BARCLAY

'A new series from Val McDermid promises to be an event - and 1979 delivers. Full of wit, thrills and incisive social observation and features a marvellous new character to follow through the years to come' MICK HERRON

'Absolutely fantastic. I have been reading Val McDermid for twenty-five years, so I am really saying something when I tell you I enjoyed this novel the most' CHRIS BROOKMYRE

'The good news is that this excellent novel marks the start of a new series' GUARDIAN

'Brilliant characters, masterful plotting and a pitch-perfect evocation of the heyday of newspapers. I loved it' CHRIS HAMMER

'McDermid can do edge-of-seat suspense better than most novelists . . . An excellent opener to what promises to be an outstanding series' SPECTATOR

'A gratifyingly multi-faceted character' FINANCIAL TIMES

'The work of a writer at the peak of her powers' HERALD

'The fast-paced storytelling flows irresistibly' IRISH TIMES

'A pacey read' DAILY EXPRESS

'A sensational novel. A surefire bestseller from one of Britain's most accomplished writers' SUNDAY EXPRESS

'A nail-biting new series' OBSERVER

'The Crime Queen has done it again and created a character we will all come to know and love. A masterpiece' DAILY RECORD